Recapitalising the Syrian Banking System: Costs & Challenges

by Andrew Cunningham with Darien Middle East

It is hard to think about reconstructing Syria and its economy at a time when there is so much uncertainty about how the civil war will develop in the months ahead, but, as the fiasco of Iraqi “reconstruction” in the months following the overthrow of Saddam Husain has shown, failure to plan for the days when the conflict has ended will not only delay the process of reconstruction but may also lead to a continuation of bloodshed and violence.

It is in this context that Darien Middle East has developed an analysis of the costs and challenges that will likely be involved in the reconstruction of the Syrian banking system, building on our June 2013 analysis “Deconstructing the Syrian Banking System” (on Syria Comment; also available on the Darien website).

In terms of costs, we estimate that $10.5bn – $16bn will be needed to recapitalise the state-owned banks. This is about 20 – 30% of pre-civil war GDP. It is an amount of money that would not preclude a rapid recapitalisation, if western powers are willing to provide financial and technical support for the process.

As for the principal challenges that will be faced, much will depend on whether a strong government emerges from the conflict – one that is able to take and impose decisions reasonably quickly; or whether a post-conflict government is characterised by factional fighting. In the former scenario, reconstruction, including bank recapitalisation, will be a largely technical affair and can be achieved fairly quickly; in the latter scenario, reconstruction will be a hostage to political interest trading and is unlikely to progress quickly.

Three Stages to Quantifying the Scale of Bank Recapitalisation

The process of rebuilding the Syrian banking system falls into three areas:

-

First, we must take a view on the level of losses in the banking industry prior to the conflict.

-

Second, we must consider the extent to which such losses will have been increased by the conflict.

-

Third, we must consider the medium and long-term capital requirements of banks in post-conflict Syria.

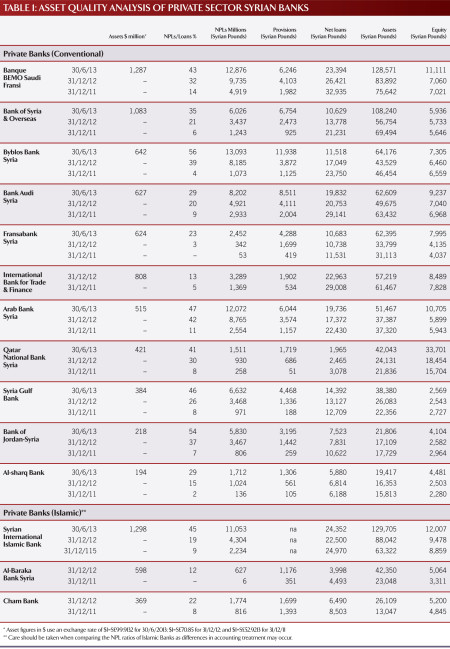

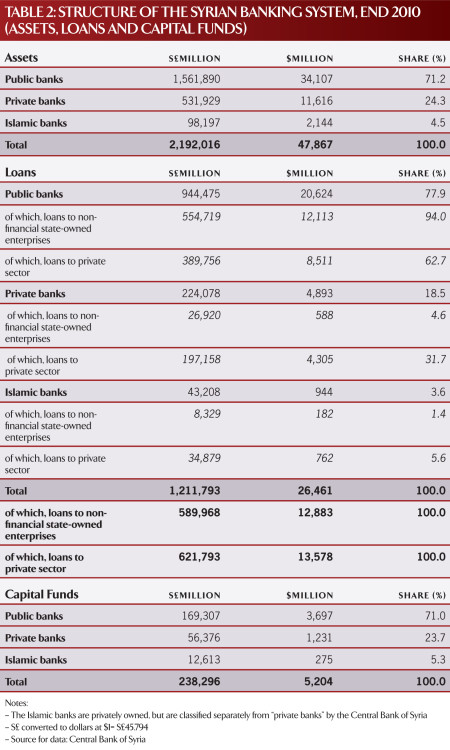

Our analysis addresses only the state-owned banks in Syria. Private sector banks are likely to have been more solvent than state-owned banks going into the current crisis, since they are able better able resist pressures to lend to poorly performing state-owned enterprises. Private sector and Islamic banks accounted for only 6% of lending to state-owned enterprises at the end of 2010, although their share of banking system assets and of capital funds was nearly 30%.

Furthermore, private sector shareholders tend to take a more realistic approach to potential losses. Those that are subsidiaries of foreign banks will have been required by regulators in their home countries to make adequate provisions against losses.

Table 1 – click for full-size image

Table 2 – click for full-size image

If private sector banks need to be recapitalised, the funds will come from their owners and not from a future Syrian government or the international community.

The six state-owned banks account for nearly three quarters of all banking assets in Syria. The Commercial Bank of Syria accounts for about half of the combined assets of these six state-owned banks, and the Real Estate Bank about 15%.

Estimating the True Level of Non-Performing Loans

Estimating the cost of bank recapitalisation entails making some bold assumptions, the most important of which is about the level of losses that banks will be facing when the conflict ends.

The IMF’s 2009 Article IV report on Syria gives the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to total loans at the state-owned banks as 5.9%. This figure, which the IMF sources to the Central Bank of Syria, is not credible. One must assume that the state-owned banks began the civil war with substantial undeclared credit losses on their balance sheets.

By way of comparison, the World Bank estimates that about a quarter of loans extended by Egyptian banks (both public and private) were non performing in 2005 before the Egyptian Central Bank began to clean up the banks’ balance sheets. The World Bank estimates that the NPL ratios of Tunisian banks were about 12% before the overthrow of Ben Ali, and puts the current ratios of banks in Jordan at about 8% and Morocco at about 5%. Tunisia, Jordan and Morocco have well-supervised banking systems and powerful central banks.

The Iraqi banking system provides a demonstration of how difficult it can be to estimate the extent of losses in a post conflict society. Work to rehabilitate the Iraqi banking system began soon after the overthrow of Saddam Husain in 2003 and picked up pace when the World Bank signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Central Bank of Iraq in 2006. Efforts focused on the two commercial banks, Rashid and Rafidain, which accounted for 90% of banking activity in Iraq. Yet seven years later, in its July 2013 Article IV Report on Iraq, the IMF was acknowledging that the net worth of the two banks remained difficult to estimate due to lack of transparency and the continuing presence of pre-2003 items on their balance sheets.

So, what is a reasonable estimate for loan losses in Syrian commercial banks?

At the end of June 2013, the median non-performing loan (NPL) ratio for privately owned banks that had published their full financial statements either on their websites or with the Damascus Securities Exchange was 43%. This compared to 21.5% for all such banks at the end of December 2012, and 7.5% at the end of 2011. Private sector banks can be expected to display stronger asset quality (i.e. lower NPL ratios) than the state-owned banks.

By way of comparison, Commercial Bank of Syria, the leading state-owned bank, reported a non-performing loan ratio of 3.5% at the end of 2011 (stating NPLs at S£12 billion, $227mn), compared to 1.6% at the end of 2010. The Real Estate Bank, reported an NPL ratio of 6.5% at the end of 2011 (stating NPLs S£685mn, $13mn) compared to 3.6% at the end of 2010. None of these figures is credible.

Taking into account the published non-performing loan ratios for the private Syrian banks; the figures from other state-led economies in the Middle East, such as Egypt; and the probable impact of a drawn-out civil war in Syria; it is reasonable to assume that between one half and three quarters of all loans extended by the state-owned banks will be impaired.

Of course, not all impaired loans entail a write-off of all funds owed. Loans can often be rescheduled, customers can be coaxed into repaying a proportion of what they owe in return for forgiveness of the rest, and sometimes banks can seize and then liquidate collateral. The recovery rate on impaired Syrian loans is likely to be low, but it will not be zero, especially in the case of loans to sate-owned monopolies that are likely to remain in business after the fighting ends.

In the past, the level of provisioning by state-owned banks against their non-performing loans appears to have been modest. The IMF estimated that provisions covered about one sixth of the gross non-performing portfolio in 2008 and 2009, and about 1% of the gross loan portfolio – in simple terms, about $200mn.

Syrian Banks Will Need Extra Capital to Raise Lending Rates during Reconstruction

Having predicted the unrecoverable portion of non-performing loans at the end of the conflict, and written those amounts of against existing capital funds, one needs to look ahead to the capital levels that banks will need to operate safely in future and also to meet the huge demands for finance that will arise during the reconstruction phase. Our analysis assumes the need for an un-weighted leverage ratio of 8%. This is high by international standards, but fair for Syrian banks.

As for the level of future lending, one must assume that after the conflict has ended Syrian banks will need to provide large amounts of money to fund reconstruction projects and enable new businesses to be established. Historically, Syrian banks have not lent as much to Syrian businesses as banking systems in other Middle Eastern (or other) countries have been lending to businesses in their own countries. Throughout the Middle East, bank lending is generally equivalent to about 55% of a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) according to the IMF. In Syria, this figure was about 40% in 2010, according to our calculations. So if Syrian banks are to play a full role in the country’s reconstruction they will need to increase their rate of lending, and to do this they will need more capital.

Based on these assumptions – the likely level of loan losses (50% – 75% of the loan portfolio is impaired and a significant proportion of that is unrecoverable), a capital requirement that can be considered prudent (an 8% un-weighted capital ratio), and a convergence by Syrian banks to the lending levels seen elsewhere in the Middle East (55% of GDP), we estimate that the cost of recapitalising the state owned banks is likely to range from $9bn to $16bn.

——————-

Supplemental: Steps to Recapitalise a Banking System

Recapitalising a banking system is not a fundamentally hard thing to do. It entails reaching a realistic valuation of the assets on banks’ balance sheets, deciding who is going to pay the difference between that valuation and the value at which the banks have been holding the assets on their books, allocating the funds to pay that difference, and then passing any regulations or laws necessary to execute the plan.

Difficulties and delays usually arise as a result of a lack of political and bureaucratic nerve or as a result of institutional obstruction by those who are vested in the status quo ante.

Finding the money necessary to recapitalize a banking system should not be a problem. In emerging markets, it is usually stateowned banks that need to be re-capitalised, and new capital can be provided in the form of government bonds and guarantees.

Issuing such bonds and guarantees increases the level of a government’s debt (as we have seen in Europe, as national governments moved to bail out insolvent banks), but robust analysis should already have factored in a government’s contingent liability to insolvent state-owned banks, with the result that a government’s economic debt ratios (as opposed to published debt ratios) change little after a bank bail-out is executed.

In the case of Syria, injecting $10bn into the banking sector would approximately double the country’s public sector debt. (Pre-civil war GDP was about $50bn and pre-civil war debt to GDP was about 20%.) When viewed against the cost of other emerging market bank bail-outs, such numbers are not prohibitive. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that as a result of sanctions the Syrian government’s obligations to western countries have been diminishing – so making the assumption of new debt easier to bear; and also that western governments would financially support the recapitalisation of the Syrian banking system under a post-Asad secular government.

That said, experience tells us that the key factor determining the extent to which the Syrian banking system can be transformed after the civil war, and the pace at which such transformation will occur, will be the political environment in which such transformation begins, rather than the financial cost of bank recapitalisation.

Efforts to recapitalise and modernise the Iraqi banking system began fairly soon after the overthrow of Saddam Husain in 2003. In their first years, such efforts achieved little and even now the Iraqi commercial banking system remains hugely dysfunctional and a weak engine for economic growth. (At the end of 2012, Iraqi banks’ loans to the private sector represented about 17% of their assets and were equivalent to about 8.5% of Iraqi GDP.)

There have been three key reasons for the slow improvement in the quality of the Iraqi commercial banking sector.

Firstly, efforts to reform the commercial banks had to start from a very low level – the Iraqi economy had been subject to wide ranging international sanctions for 13 years before the overthrow of Saddam in 2003 and prior to that the banks acted primarily as the tools of government rather than as commercial enterprises.

Secondly, the Central Bank’s ability to act decisively was constrained by rivalries and conflicts within the Iraqi government. In particular, the Central Bank and the Ministry of Finance had a difficult relationship. (In 2012, the incorruptible Dr. Sinan al-Shabibi, who had fought to maintain the Central Bank’s independence, was removed from the Governorship by Prime Minister Maliki.)

Thirdly, the high level of violence and insecurity throughout the country hampered day to day work, particularly of foreign experts trying to provide advice and guidance – if a visit to a bank is only possible when one travels by armoured convoy, the number of such visits will be limited and the quality and quantity of time spent advising local bank staff will be compromised. The security situation also prevented experienced Iraqi expatriates from returning to Iraq to work in banks.

Egypt provides a contrasting picture, albeit one which provides an inexact comparison. When the Central Bank of Egypt began its bank reform programme in 2005, there were already well-performing, privately-owned banks operating in Egypt that could provide examples of good practice, and occasionally supply experienced commercially-minded staff to the state-owned banks. Furthermore, the Central Bank enjoyed the full support of the Ministry of Finance and the highest levels of government. And of course, Egypt was peaceful. The biggest constraints to getting advice into the banks seemed to be the Cairo traffic jams! (The author speaks from personal experience!)

Why does capital matter?

Capital is a bank’s cushion against unexpected losses; as opposed to provisions, which are its cushion against loan losses that have already occurred or which are expected to occur. When a bank recognises loan losses, it writes down the value of those loans in its financial statements. If the losses so great that they overwhelm the bank’s loan loss provisions, the only way to balance the accounts is to write down the value of capital. If a bank depletes its entire stock of capital then it is deemed to be insolvent and should be closed down by its regulator (because having depleted capital, it will only be able to balance its books by defaulting on deposits or bonds). Even if a bank has positive capital, the regulator may still have reason to close it down, since all banks should maintain a minimum level of capital today to protect against unexpected losses in future.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which sets international standards for banks, has called for regulators in require a minimum leverage ratio (that is, a ratio of capital to unweighted assets) of 3%. However, it is widely expected that regulators in underdeveloped or risky banking systems will require leverage ratios significantly above 3%.