Akram al-Hawrani: Syria’s left-wing populist and the United Arab Republic

By Christopher Solomon – For Syria Comment – February 15, 2017

Gamal Abdul Nasser (left) with Akram al-Hawrani (center) and Egypt’s Abdul Latif al-Baghdadi (right).

As the pro-Assad forces recaptured the last sections of rebel-held Aleppo in December, they excitedly declared that these areas now had “green eyes” (eyoon khadara) in reference to the twin green stars found on the national flag. Now heavily associated with President Bashar Al-Assad’s Baathist government, the flag’s origins can be traced to the United Arab Republic (UAR), which was founded in February 1958 and last until September 1961. The green stars represented Syria and Egypt’s unification and the tricolor served as inspiration for several other Arab countries with Pan-Arab ideological foundations. For the Baath Party, this union was the long-awaited realization of their key political tenant which would propel the Arab World towards unity.

The UAR flag that flew over Syria from 1958 to 1961 and now currently in use since 1980

The UAR flag that flew over Syria from 1958 to 1961 and now currently in use since 1980

Recently, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi has slowly begun to depart from the stance of the rest of the Sunni Arab bloc and rebuild ties with Assad’s government. There has been a noted emphasis by

Egypt on the need for enhancing bilateral security and military cooperation. What this means for Syria in the remaining years of the conflict and, eventually the post-conflict era, is not yet clear. The history of Egyptian-Syrian relations is long, at the center, looms the UAR. In order to understand Syria’s place in the UAR, its importance for the Baath Party’s history, and its impact in the social and political direction of the country, one should look to Akram al-Hawrani, now a relatively obscure personality in more recent Middle Eastern history, as an important and revolutionary Syrian political figure of this bygone era.

Early Life in Hama

Hama in the 1950s

Hama in the 1950s

Hasan Akram al-Hawrani was born in 1911 to a respected Sunni family which followed a Sufi religious order that emphasized helping the poor and disadvantaged. His father, Rashid al-Hawrani, was a textile weaver and upon entering local politics, won a seat on the Hama City Council. Hawrani’s childhood had seen his family’s wealth squandered and he subsequently grew up loathing the land owning elite that dominated the countryside. Hawrani’s life in politics began in the city of Hama as a social leader and agitator. The center of his focus were the elite Hama area families – the Azms, the Kaylanis, and the Barazis – who ruled over the region with ruthless and unchecked power. They controlled over 100 villages and had their own private armies to enforce their will. It was Hawrani’s tireless quest during the backdrop of this extreme class divide to fight and to obtain social justice for Syria’s rural peasants that won him vast popularity with Syria’s poor and impoverished. In his home city, Hawrani would build his populist movement into a force to be reckoned with that radically influenced and changed Syria’s society and politics. Hawrani had taken the reigns of leadership over the Youth Party of Hama that had been founded by his cousin, Uthman al-Hawrani. Violent battles between Hawrani’s movement and the landowning families were frequent. His early victories against the Landowner’s paid thugs won him widespread praise. Likening him to knights of old, common people wore badges with his picture and hung his photo in their homes.

Onset of Nationalism

Aside from social justice, Hawrani had strong nationalist sentiments as well. His childhood memories recalled the 1920 French’s victory which destroyed the short-lived Arab Kingdom of Syria that had been established after World War I by Faisal bin Hussein. When the 1941 Rashid Ali revolt broke out in neighboring Iraq, Hawrani used his connections in the Syrian army to recruit officers to join him in the fight against the British. When the revolt failed, he was captured by the French upon crossing the border and was detained at their desolate military base in Deir el-Zor for a short period of time. Among his cellmates were two other figures who would later become central leaders in the formation of the UAR, the Baathist thinker Dr. Jamal al-Atasi and the leftist army officer Afif al-Bizri.

Flag of the Arab Kingdom of Syria, from which the Pan-Arab colors are derived, lasted only a few months, from March to July of 1920.

Flag of the Arab Kingdom of Syria, from which the Pan-Arab colors are derived, lasted only a few months, from March to July of 1920.

Hawrani also was known to have used his early affiliation with the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) which he viewed primarily as an opportunity to cement his anti-Imperialist credentials and to bolster his movement. It was the party’s militant nature that appealed to Hawrani along with its desire to end foreign domination in the Levant, to eradicate feudalism, and to establish a secular and socially progressive state.

To cover up his activities with the SSNP, he established the Arab Socialist Movement. In reality, Hawrani’s ties to the Pan-Syrian party were relatively thin. Ultimately, he felt that the SSNP was too intellectual and cumbersome to grow into an effective mass political organization. It would be his army connections and the ideology of Arab nationalism that ultimately determined his fate in Syria’s political future.

In 1943, Hawrani secured a seat in Syria’s national parliament where he first met Michel Aflaq and Salal al-Din Bitar. Aflaq was an urban intellectual who had founded his Baath movement (Baath translates to renaissance or resurgence) in the late 1940’s in Syria’s cities, schools, and universities. Though Hawrani did not join their Pan-Arab party at this stage, he became friends with the two men and frequented the party’s headquarters in Damascus. Along with the Baath, Hawrani built ties with the Communist Party and the Muslim Brotherhood. It was in Damascus where Hawrani established a reputation as an ardent champion of freedom of speech and as a fighter, sometimes quite literally, with fist fights breaking out on the floor of Syrian parliament between him and supporters of President Shukri Quwatli’s old guard.

Being primarily active in Hama, Hawrani’s proximity to the Homs military academy made it possible to link his movement to the support of army officers nearby. He also joined his friend and military figure Adib al-Shishakli (also an early member of the SSNP) in attacking the local French garrison in Hama. These violent actions were so successful that he was instructed by Syrian independence leaders to stop since these facilities would eventually fall into Syrian hands after the anticipated departure of the French. Hawrani’s network within the army was also further extended with his participation in campaigns on the frontlines of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The full extent and endurance of Hawrani’s power base would be tested during Syria’s era of military coups.

Hawrani during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Hawrani and Syria’s military coups

Although Hawrani did not directly plan and implement Syria’s first coup headed by General Husni Ziam, he supported them politically. In his view, it was an opportunity to implement his land reform schemes. Hawrani was later able to land a spot as the general’s advisor with the help of the nationalist officers in the army. He had also channeled members of his youth movement towards careers in the military. However, it wasn’t long before a rift grew between Hawrani and Ziam. This was due to Ziam’s close ties with Hawrani’s archenemies from the old landowning clans in Hama. After Colonel Sami Hinnawi overthrew Ziam, Hawrani become the Minister of Agriculture in the new regime.

The Baath, for their part, had grown in size and popularity due to their criticism of the government’s defeat in the Arab-Israeli War. Consequently, the party was repeatedly repressed during the periods of military rule. Aflaq spent a couple spells in Mezzeh Prison in Damascus. This practice of authoritarianism was something the Baath learned from and would eventually come to utilize themselves.

It wasn’t until Hawrani’s friend Shishakli seized control that he was able to finally introduce his land reform program with the backing of the national government. Order Number 96 restricted the expansion and ability of landowners to obtain unregistered land, which was reallocated to peasants.

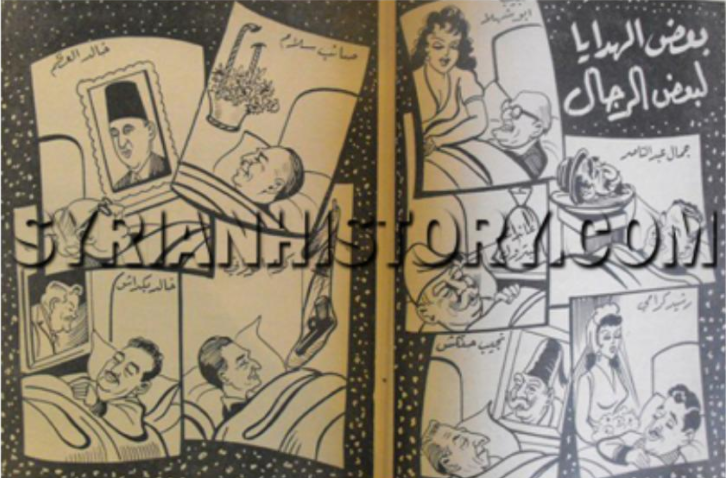

Hawrani (left page, bottom right panel) dreams of a gun to carry out a coup in this Arabic political cartoon from 1955.

Hawrani (left page, bottom right panel) dreams of a gun to carry out a coup in this Arabic political cartoon from 1955.

During the Shishakli period, Hawrani gave a speech in 1951 before a crowd of 10,000 in Aleppo, “My friends! We are weak when we are alone, but stronger than iron and fire when united! With the blood of our ancestors flowing through our hearts, we can rebel against tyranny and injustice!”

The growing use of the automobile brought about the ability to shuttle peasants on buses from the countryside to the cities to attend political demonstrations and thus project a show of force. It also served to add new members to his party. The Arab Socialist Party grew by merging the rural peasants with the urban industrial workers. In the countryside, Hawrani’s “This Land Belongs to the Peasants” campaign took a violent turn with villagers taking up firearms against the wealthy landowners.

When Shishakli began to assert his crack down on political opposition (which was largely in response to several plots against him that were uncovered) the Arab Socialist Party, along with the Baath Party, was banned. In January of 1953 Hawrani, Bitar, and Aflaq went into exile where they began to plan Shishakli’s downfall. With the support of friendly officers in the army, Hawrani, Bitar, and Aflaq were able to create a coalition (in large part with help from the military) that opposed Shishakli’s rule from exile and force him to resign. The trio returned to Syria where the country experienced a brief revival of democracy.

In the years that followed his overthrow, Shishakli traveled to Beirut to discuss the potential coup with the SSNP against the Syrian regime, his old friend and associate, Hawrani, was allegedly one of the names compiled on the hit list for the SSNP’s assassination squads. However, Shishakli’s coup plans with the SSNP never materialized.

Hawrani (left) with Salah al-Din Bitar (center) and Michel Aflaq (right) in exile in Rome during the Shishakli period

Hawrani (left) with Salah al-Din Bitar (center) and Michel Aflaq (right) in exile in Rome during the Shishakli period

In 1952, while in exile in Lebanon, Hawrani had reached an agreement with Aflaq to merge the Arab Socialist Party with the Baath Party, thus becoming the Arab Socialist Baath Party, the name by which it is known today. The marriage of rural peasants and poor laborers to the student and urban intellectuals turned the party into the mass popular movement it had to become in order to secure and sustain power. This merger was officially blessed during the Baath Party’s 2nd Congress in 1954 that followed the overthrow of Shishakli.

A Baath Party Logo showing the Arab World united

United Arab Republic

Hawrani seated next to Abdel Nasser during a meeting with Lebanese leaders on the Syrian-Lebanon border following the 1958 Lebanon crisis. Note the appearance of the two starred flag of the UAR.

Hawrani seated next to Abdel Nasser during a meeting with Lebanese leaders on the Syrian-Lebanon border following the 1958 Lebanon crisis. Note the appearance of the two starred flag of the UAR.

Following the Suez War of 1956, there was a renewed push within Syria to move ahead with the proposed union with Egypt. Dr. Jamal al-Atasi touted the pro-Nasserist line through the party newspaper. Afif al-Bizri, with his strong leftist leanings, was now chief of staff in the army. He was instrumental in packing the army with pro-Nasser officers. Furthermore, Bizri led purges against politicians with anti-Nasser sentiments. Bizri’s supposed communist ties generated much fear in the West that Syria was quickly becoming a Soviet satellite state. The purges led to a moment of heightened tension in the Cold War which subsequently saw Egyptian troops land in Syria in order to check the mobilization of Turkish troops along Syria’s northern border.

Syrian women of the Popular Resistance Committees during the Suez War shows Hawrani’s wife, Naziha al-Homsi (center) in 1956

Syrian women of the Popular Resistance Committees during the Suez War shows Hawrani’s wife, Naziha al-Homsi (center) in 1956

Syrian Communist Party leader Khaled Bakdash (second on the right) and his wife, Wisal Farha Bakdash, with a Chinese delegation in 1957

Syrian Communist Party leader Khaled Bakdash (second on the right) and his wife, Wisal Farha Bakdash, with a Chinese delegation in 1957

Meanwhile, the competition between the Baath and the Communists was increasing dramatically. Each side had their own views on how to implement a union with Egypt and Khalid Bakdash, the head of the Syrian Communist Party (SCP), personally disliked Nasser due to his frequent imprisonment of Egypt’s communists. The challenges from the SCP brought about pressure from the Baath’s own left flank which caused the party to struggle with internal divisions. A critical turning point for the Baath Party and Hawrani’s political future was his decision as Speaker to cancel the Baath’s participation in the November 1957 elections. Hawrani used his position as the Speaker of Parliament to forge ahead with the formation of the UAR, becoming the Vice-President in Nasser’s UAR government.

Stamp with the date February 1, 1958 showing a bridge linking Syria and Egypt with the inscription reading al-Jumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-Muttahidah (United Arab Republic)

Stamp with the date February 1, 1958 showing a bridge linking Syria and Egypt with the inscription reading al-Jumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-Muttahidah (United Arab Republic)

For his part, Nasser had preached for Arab unity but was quietly skeptical since he was personally opposed to the practice of political pluralism. In order to achieve their goal of Arab unity, the Baath Party made the hard decision to suspend all party activity as demanded by Nasser. For Bakdash, the decision to disband the SCP was an ideological anathema. His continued protests during the UAR years brought about a crackdown against the communists which in turn led Bakdash to leave Syria for safety in the Soviet Union.

Though many Syrians had long waited for a union with Egypt, the new life in the UAR was not what many had expected. Syrians found Nasser’s rule to be far more politically repressive than anything they had experienced under Shishakli. With the help of Nasser’s Syrian ally, Colonel Abdul Hamid Sarraj, their country had essentially become a police state under the domination of Egypt. In addition, Nasser’s heavy-handed rule brought about much disenchantment with the union and his extreme nationalization policies alienated many former supporters in the business community and the army.

Political Exile

Although Hawrani had been instrumental in the creation of the UAR, he began to fall out with Nasser who had eventually turned his sights on the Baath. Disillusioned with the UAR project, Hawrani made the fateful decision to add his name to the document in circulation that would bring about Syria’s succession and lead to the dissolution of the UAR. For the Baath, this move would dramatically change the face of the party. In 1961 the Syrian army implemented a successful coup which forced the Egyptians out of Syria. Egypt returned the favor by expelling the nearly one thousand Syrians working in various government or military positions in Cairo back to Syria. One of these men was a young Alawite air force officer named Hafez al-Assad.

For the Baath Party this was a painful period where the long awaited dream of forming an Arab federation was now dashed. For many party members, especially the young military officers, they still held strong pro-Nasser sentiments and soon aligned themselves with the remaining Nasserist elements in Syria. This brought about the 1963 Neo-Baathist coup that overturned the secessionist government. The small and tentative steps towards returning democratic practices to Syria were destroyed.

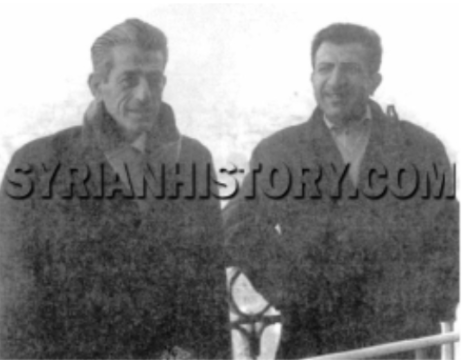

Akram al-Hawrani in exile in his later years with a friend in Strasbourg, France in 1972

Akram al-Hawrani in exile in his later years with a friend in Strasbourg, France in 1972

Hawrani’s personal support within the Baath was destroyed as well. His name had been attached to the secessionist movement and he was never able to recover from this stigma. Hawrani reestablished his Arab Socialist Party but, as the Neo-Baathist commenced their purges, he left Syria again for good, living his remaining years in exile until his death in 1996. However, the Neo-Baathists were ultimately unable to reignite the UAR project. Syria would soon divert its focus from Pan-Arabism to objectives closer to home, eventually aligning the Baath’s emerging geopolitical interests in Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel with the SSNP.

Many historians have argued that Hawrani was within a hair of becoming the Syrian Fidel Castro. For Hawrani’s ideology was not built on the direct influence of Marxist thought but rather through his own values and interpretation of Arab culture and religion, along with his political experience which was formed during his time with the SSNP. The Pan-Syrian party had regarded feudalism as a foreign invention that would forever keep the Arab World in a socially regressive state.

Hawrani’s war on feudalism forever changed Syrian society and politics. Hawrani’s speeches mobilized thousands of disadvantaged minority sects into influential positions in the military (Hafez al-Assad, being a poor rural Alawite, was one of the people who answered Hawrani’s call) and took on the foundations of Syria’s stuffy, old Sunni merchant elite. He transformed the Baath Party into a populist party that was able to capture the imagination of masses and establish a political union that was once unthinkable.

Now, once again Syria and Egypt are taking tentative steps to build a relationship in a time of rapid change and political uncertainty. As the Syrian government continues to battle the remaining Islamist factions and confront Kurdish aspirations, Egypt will continue to step into the picture, lending its political and military support.

The UAR and its flag only lasted a few years before the Baathist Pan-Arab dream ended, and with it, much of its original ideological composition. The party soon became an organizational tool for Assad’s governing structure. It may have been the Neo-Baathist under Hafez al-Assad that would later resurrect the UAR flag by hoisting it as Syria’s official flag in the 1980’s, however, it was Hawrani and his time in Syria’s echelons of power that set about the political trajectory for the country. For now, the flag of the United Arab Republic survives, unlike the union it once herald into existence, and will likely to continue fluttering over Syria, along with an unknown future for the government it now represents.

*Christopher Solomon is an analyst with Global Risk Insights. Chris traveled to Lebanon and Syria in 2004 with the CONNECT program at the University of Balamand. He earned his MA from the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) at the University of Pittsburgh. He also interned at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC. Follow him on Twitter @Solomon_Chris

The post Akram al-Hawrani: Syria’s Left-Wing Populist and the United