MESOP UPCOMING DVD – FILM : “Comrade, where are you today” – Biography of certain wellknown Lefties

Marxist-Leninist nostalgia

“EVERYONE is good and bad,

Everyone is ugly and beautiful,

Everyone is fat and slim,

Everyone is happy and sad,

Everyone loves everyone.”

Kirsi Marie Liimatainen wrote the little poem when she was eight. Now a film-maker living in Berlin and Helsinki, she was born in 1968 in Tampere, a town nicknamed the “Manchester of Finland” for its industrial past. “We were really poor,” she says. Her poem introduces her documentary “Comrade, Where Are You Today?” which premiered in Berlin on August 11th.

“There were two possibilities for poor people in Finland: One either went to church or to the communists.” Her grandparents decided for the latter. “They wanted a paradise on earth, and not after death.” Ms Liimatainen’s grandmother participated in strikes for better working conditions in her factory, and taught her granddaughter to read the “Communist Manifesto”, and the left-leaning as well as the conservative press. Following in her mother’s footsteps, Ms Liimatainen joined the Pioneers, a communist children’s organisation, and she was proud of her red neckerchief. “We demonstrated for peace and collected money for poor children, which allowed them to spend their summer holiday in a Pioneers’camp for free. We occupied houses since there was a shortage of flats to rent in Finland…I joined hunger strikes against government plans to cut subsidies for young and long-term unemployed people.”

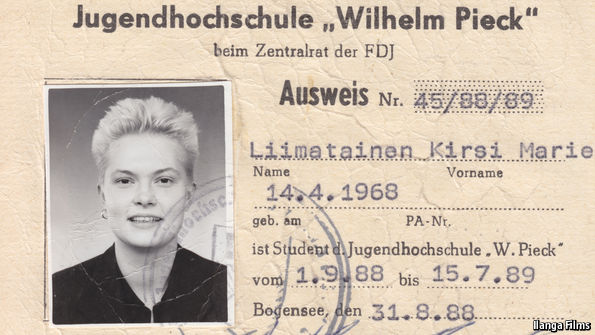

Jobless and eager to learn about the “real existing socialism” the East Germans boasted of in magazines distributed in Finland, a young Kirsi went to East Germany to study Marxism-Leninism. In summer 1988 she arrived at Wilhelm Pieck College near the Bogensee, a lake some 25 km north of East Berlin run by the Free German Youth (FDJ), a communist youth organisation. The huge grounds of the “cadre forge” for future communist leaders included the villa of Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister. When the Soviet forces handed over the area to the East German youth organisation in 1946, the first seminars were held in the building. Houses were built later. Students from 80-odd countries studied there each year until the Wall came down in autumn 1989. Ms Liimatainen’s year was the last one.

She was captivated and deeply impressed by the spirit of solidarity there on the Bogensee. She was curious and visited youth clubs and discotheques in East Berlin at weekends where she met young people who did not join the FDJ. She soon realised she was not in a workers’ paradise, and quickly came to understand why East Germans were protesting for the freedom to travel and to express their opinions.

The Wall fell, Germany reunited, the German Democratic Republic ceased to exist and the school closed. Since then, the complex has turned sleepy. Bushes and trees grow out of the cracks of the run-down premises, as if burying the socialist project itself. Although the communist bloc collapsed, Ms Liimatainen remains convinced there must be an alternative to capitalism, which she sees as profit maximisation for a few and poverty for the many. The growing gap between rich and poor encouraged her to make a film about the old left, and what had happened to her fellow students. Where were they now, and what remained of their values and dreams?

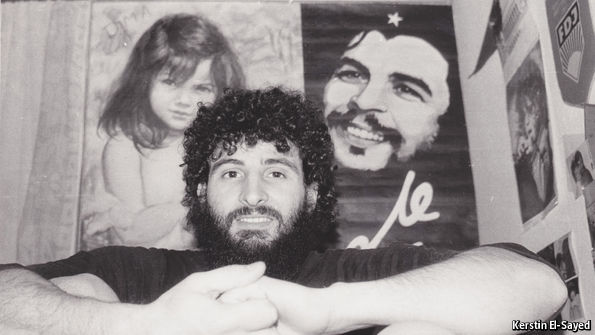

Finding former underground organisers and even armed fighters who had had to hide their real names wasn’t easy. The East German archives had no files about her school year, not even about her. And yet Mrs Liimatainen tracked down four of her former friends: Lucia, whose real name turned out to be Nidia, in Bolivia; Esteban (really Marcelino) in Chile; and Ghazwan and Nabil (pictured above, with a poster of his hero Che Guevara), in Lebanon. The search for Duma, a charismatic South African and back then a clandestine fighter for the African National Congress, turned out to be the hardest, since the ANC still uses “combat names” to protect former soldiers. She came to South Africa too late. Themba, as Duma turned out to be named, had died in 2003, his wife tells her at his gravesite in Soweto. It is the widow’s turn to be disappointed in the promise of a better future: although they are free now, she says, the country is still divided, and many members of the ANC are corrupt.

Ms Liimatainen’s documentary is an absorbing journey through the present and past of the conflict zones of the Cold War. Her remarkable historical footage, impressive new images from all the countries she visited and her pleasant, reticent narration give the viewer a balanced appraisal of the state of things today. Some goals the former revolutionaries fought for have been achieved, but injustices keep cropping up: poor education, corruption, land-grabs, inequality. The old comrades are disappointed by the failure of the socialist project, but now wiser about the reasons for it.

The journey ends where it began, at the dilapidated college in Bogensee. Ms Liimatainen ponders what she and her friends are feeling: “The images of the abandoned school tell us about a state who had forgotten its people. I do not believe that such a system will be missed. But the goals we were dreaming of then and are still dreaming of today can’t have been wrong. I still want to believe in a child’s dream of freedom and equality.”

“Comrade, Where Are You Today” will be available as DVD in January 2017. Film screenings are scheduled until mid-November in Berlin and other German cities.

www.mesop.de